This is the eight installment in the weekly Honored Role Series.

Before turning 10, Terry Tepper took the helm of the family’s 40-foot wooden yacht and steered into Barbados harbor, “My father handed me the tiller and said, ‘take her in’. He folded his arms, sat down on the bow and smiled. I backed the sails and steered her in. It was the greatest gift a child could receive — responsibility, confidence, and the first taste of empowerment.”

Four decades later, successfully at the helm of the U.S. Army’s largest medical facility, Womack Army Medical Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Colonel Terry Tepper Walters, M.D., reflects upon several horizons she navigated.

Embarking on Adventure

Born in Malta, the only child of a former British Royal Navy officer and a proper British wife (Kathleen), Terry and her family set sail around the world in 1969. Terry remembers her traditional yachtsman father sailing the channels of myriad harbors, navigating by sextant.

Two years into their global circumnavigation, the Teppers returned to the Caribbean. In St. Lucia, Captain Tepper chartered their yacht while mother and daughter stayed ashore with friends. Within days a hurricane carried away both Terry’s father and the yacht; she never saw him again. “For years I fantasized what happened. We had no closure. Everyday I am reminded of the agony of the families of Soldiers missing or killed in action, and the importance of closure,” Terry shared.

Homeless and penniless, yet believing America the land of opportunity, Kathleen took her daughter to New York where they lived with an aunt. During a weekend visit to West Point, 12-year-old Terry saluted a parading cadet. He returned her salute.

Working multiple jobs, Kathleen saved for a down payment on a small house in Elmsford, NY. When Terry entered high school, they remodeled the old house; Terry hung sheet rock, plumbed and learned carpentry. They ate plain pasta and heated a single room. Terry focused on books and sports and bussed and waited tables to save college tuition. She graduated valedictorian of her high school class and placed 6th at the 1976 Winter Olympics speed skating trials.

Entering Gates

When West Point opened to women, Terry applied, despite no desire to become a soldier. “I attended West Point because it was free and offered a challenge,” she explains. Her acceptance to the military academy was jeopardized only because Terry was not a US citizen, a requirement for entrance. She and her mother spent most of their collective savings with an immigration lawyer who successfully accelerated Terry’s citizenship application. Congressman Peyser held a nomination open for her until she became an American citizen. “In short, I started as an illegal alien who, by great luck and the help of a dedicated lawyer and public servant, entered the gate.”

“Shocking” is Tepper’s description of entrance into West Point in its first class of women. Testing her mettle, male cadets repeatedly told her she was weak, would never serve in combat and took the place of a more deserving man; Terry remained determined to prove them wrong and threw herself into competitive sports. “I had no other choice and no money to go elsewhere.” She joined track and field, excelling in javelin.

Throwing javelin required explosive power, so Terry power lifted. Her physical prowess and squatting more than 400 pounds earned respect from many skeptical male classmates. By fourth year, she won the prestigious Penn Relays with a meet record of 155 feet and was named an alternate for the 1980 Summer Olympic team.

That same year, Tepper was among 62 women from the original 119 graduating West Point. Four days later, she and classmate Wally Walters married and began their officer careers, enduring the first year of separation. Terry entered medical school in Maryland, and Wally headed to Ft. Benning, Georgia.

While West Point made Terry even more self-reliant, capable and confident, she struggled with her self-image. “Growing up without a father, going to a male dominated college, dating few men, and entering medical school, which at the time was also male dominated atmosphere, was poor preparation for learning to love myself as a woman.” Terry admitted. The academic stresses of West Point and medical school, and an arduous internship and residency, culminated in bouts of significant depression at her first duty assignment. As a physician, Dr. Walters faced the quandery of seeking help. Weights and skates became her anti-depressants.

Practicing Army Medicine

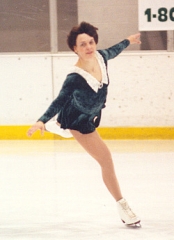

As a hospital staff internist in Ausberg, Germany in 1987, Terry won the national drug-free power lifting championships (139-lb class). The following year, she added the title of World Champion to her resume. She also became interested in figure skating.

The birth of Vikki, the Walters daughter, in 1989, changed Terry’s perspective. She explained,

“My experience at West Point made me very tough and externally confident, but it delayed my maturation as a woman and an internally confident person. Having a child and creating life is the best thing I have ever done. It cured me of self-doubt.”

Dr. Walters returned to West Point a decade after her graduation as the Chief of Internal Medicine of Keller Army Community Hospital.

When not caring for patients, Terry coached the women’s power lifting team and skated.In March 1993, Walters, then a major in the Army, deployed from West Point to Somalia as the Brigade Surgeon for the 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division, the unit designated to support the United Nations peace-keeping mission in Mogadishu.

On June 5th, Somali warlord Mohammad Farah Aideed and his forces ambushed UN and US forces killing 24 Pakistani’s and seriously wounding more than 100 soldiers. Walters, leading triage, and her small medical team raced into action.

Walter’s first patient had been shot through the ears. Although breathing, his wounds were fatal and Dr. Walters declared him “expectant”, proceeding to the next soldier. This Pakistani sustained massive trauma to his head and face after being shot in the jaw. Walters intubated him, placed him on a respirator and started several intravenous lines. She then tried to stop the bleeding with a compression bandage placed against his head; this stopped some of bleeding, but blood spurted out of his mouth. She packed the gaping hole in the roof of his mouth with gauze. The third soldier had been shot through his eye, destroying the left side of his face. At one point, 11 patients needed ventilators; they had only 10 machines. One medic ventilated a patient by hand for hours.

Thirty-six hours of triaging and treating causalities provided life-saving care to most soldiers; Walter’s team accomplished this feat, in spite of severe resource constraints and hindered conditions. Only two US soldiers suffered wounds that day, but many more causalities came in impending months.

“Although horrible, terrible, dangerous and exhausting, it was one of the most defining experiences of my career,” Dr. Walters recalled. The lack of medical strategy input into military operational planning convinced Walters that leadership was essential to ensure military medical readiness. Walters transitioned from health-care provider and physician to a commander. “I saw problems and system-wide opportunities to improve care to soldiers on the battlefield,” she explained.

Completing a masters in Public Health, Lt. Col. Walters became Division Surgeon for the 25th Infantry Division (Light) at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii and Commander of the Schofield Barracks Army Health Clinic. Once again, Walters put the edge on ice for stress relief and won the US Figure Skating Association Adult National Championship in her 35-45 yr old age group. “Winning was the biggest athletic thrill not because of winning, but for performing a perfect program. The most significant challenge in skating is overcoming one’s nerves. In power lifting, being nervous makes you stronger. In figure skating practice I had performed perfectly, but I had never done so in a competition. When I stepped onto the ice in Lake Placid, I was in the zone. My two favorite sports are complementary, albeit not so in attire. My explosive jumps on ice resulted from squatting 415 pounds in the gym. Ultimately, it was about conquering fear and being in control of myself.

At the helm of the 1st Medical Brigade based at Fort Hood, Texas, Col. Walters led one of the Army’s largest and most diverse medical brigades during combat operations in Iraq. The brigade included more than 4500 soldiers and civilians providing combat medical care in four combat support hospitals, three medical battalions, seven separate line companies and nearly 20 specialized detachments spread out from the south of Baghdad to Mosul, an area roughly equivalent to the state of Texas.

With lessons learned from Somalia and the first Gulf War, the combat medical care focused on training forward surgical teams to treat and stop bleeding, treat shock and ensure a robust air evacuation process. Walters highlighted the Air Force’s new role in transporting critically wounded soldiers to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, Walter Reed in Washington, D.C., or Womack, enabling delivery of definitive surgery within 24 hours.

Walters described, “Initially, our medics did not carry and were not trained to use tourniquets, because the loss of blood flow is the loss of limb. But the majority of injuries are from bullets, shrapnel and bombs. Stopping bleeding is paramount. We refocused on the ABC’s – secure the Airway, control the Bleeding, and ensure Circulation.”

With on-going combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, Col. Walters emphasized that lives of more soldiers are being saved than ever before in the history of warfare. “Soldiers are living today who would have died five years ago,” she offered. Although a success, the severity of combat-related injuries has changed dramatically. and we are not prepared to deal with the lengthy and difficult rehabilitation.”

Another First

In 2006, Col. Walters became the commander of Womack Army Medical Center at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, the largest military hospital. Walters is the first woman to have held the position.

During her time at the helm, Terry charted a new course and navigated the creation of a warrior transition unit dedicated to providing comprehensive rehabilitative care to severely wounded and ill Soldiers.

Both the legacy and paradox of this war is that more Soldiers are being saved by body and vehicle armor, and improved medical care and technology. But many, she emphasized, have sustained significant brain trauma from proximity to explosions and yet have no visible physical wounds. “There is a lot of pressure and air being moved in an explosion. This wave of pressure moves through brains and leaves holes.”

After World War II. the Army had several rehabilitation hospitals around the country. As the need for these services disappeared and budgetary pressures appeared, centers were eliminated. Walters explained, “There was an expectation that these Soldiers, as they have in previous wars, would go straight through the system and go to the VA (Veterans Administration). The VA has focused on its aging veteran’s patient population and did not need to treat young soldiers injured in combat. Previously, this need did not exist because soldiers did not survive these injuries. This is a new mission.”

The Army recognizes the need, and resources adjusted to the severity of injuries sustained and lengthy rehabilitation requirements. But assets and trained professionals do not just appear.

New Horizons

Approaching retirement following thirty years in the Army, Terry is charting a new course while still focused on Soldier care.

Terry acknowledges that she has achieved both professional and athletic success. Balancing work and family these past 30 years of marriage and 12 years of separation challenged both Terry and Wally.

“I have been too much a loner and concentrated on success rather than nurturing friends. When I retire from the Army in June, I look to pursuing a medical policy job in the government focused on those who have fought and bleed for our country, volunteering in my community, and forming a network of friends.”

If you would like to share your story or that of another veteran women, please contact me. Part 9 of the Honored Role series will feature a former Army officer who teaches high school physics.

[…] Col. Terry Walters, MD – Navigating Unchartered Waters [1] Lockwood, Penelope. (2006). “Someone like me can be successful”: Do college students need same-gender role models? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 36-46. […]